December 31, 2022

Drinking coffee in Kyiv, my friend the physical therapist says we all have PTSD. I’ve never been a fan of diagnoses. This is both a gift and a fault.

It’s warm at home and the lights are on. No words can describe how tired I am.

On Monday I met a soldier who had shrapnel lodged in many parts of his body for a couple months while he was a prisoner of war. They were surgically removed only after he returned to Ukraine in the fall.

Sitting in a cafe I marvel at this tall young man, still underweight, with bright intelligent eyes. He came in on his own two legs; it’s the third day he’s walking unassisted. After the explosion that filled his body with shards of metal and glass he could only move his head.

“What did you do to get from that state to this?” I ask in wonder, watching his hands and fingers move lightly, same as anybody else’s.

We talk about how the body naturally repels foreign objects; small pieces of metal or glass would gradually migrate toward the surface of his skin. “And you pulled them out with your fingers?” Yes, he says, and smiles.

*

My grandmother is missing the nail on one of her big toes – the result of an infection that appeared just after the war. She was moving westward through Germany to avoid Soviet forced repatriation, sleeping in fields and dirty vacated barracks, eating old potatoes or whatever her band of young traveling companions could scavenge. It was becoming too painful to walk when she happened upon a doctor who had the instruments to remove the infected part of her toe.

Growing up in the US, I was hungry for stories from the war. I yearned to understand what it was like, what happened there. What did people go through that afterward they were so reluctant to talk about? All they told me – with utter conviction – was, “May you never have to see what I did.”

*

There is a threshold between comfortable, clean, civilized life and the brutality of war. From the vantage point of the former, the border may seem solid, even permanent. Anyone who has crossed it by chance knows that it can be shattered in an instant.

I remember the woman from Mariupol who agreed to be interviewed for French television in March, just after arriving at the train station in Lviv. Her willingness to talk and her insistence hinted that she was well off. Hanna was a lawyer, now bound for Bali after spending three weeks in a dark basement as her city was bombed relentlessly by the Russians. Deprived of light, they were afraid they would go blind. She had a message for the Red Cross and every international body: “Use your influence to get people out of Mariupol. These people want to live!”

Tens of thousands of Mariupol’s residents have died. Those that remain in the city are wintering in apartments whose shattered windows are covered in flimsy plastic. The occupying Russian forces are renovating the Drama Theater that they bombed in the spring, killing hundreds who were sheltering inside. We will never know exactly how many people died in the city or what they experienced before their deaths.

*

Thursday morning I took a cab to a doctor’s appointment, chatting excitedly with everyone I met, we were all a bit on edge following Russia’s missile attack. By afternoon I’ve already forgotten about the four explosions I heard in the morning.

When the body is constantly at the mercy of the environment, whether this means protecting yourself from Russian strikes or catching the light to have a warm shower, you enter a state of being more agitated and alert, quick to speak and act, impatient to the dull softness that is the privilege of living in a country protected by a nuclear arsenal.

This kind of physical knowledge changes you, even if you still remember how to act civilized. You might blend right in but nobody knows where you’ve been and even if you try to say it in words they understand, they remain on that side of the wall, and your excruciating job is to be a translator.

One gets used to living in inconsistency, to not being able to depend on anything or anybody. I feel changes in temperature, tiredness, anger. Not much else. But if the soldier I met could recover his movement enough to step onto the fast-moving escalator of the Kyiv metro, I’m sure I’ll regain the ability to feel when it becomes relevant again.

*

A person flees from a war zone dirty, smelly, terrified. And then you wash them, feed them, give them a clean, warm place to sleep. And they still have the war with them. Everything they lived through.

A woman at a weekly support group for IDPs shares: “I don’t like that I hate. I don’t like that they have made us hate.”

When my grandparents despised the Russians it wasn’t through prejudice. It was a judgment based on experience.

Is the wish to permanently secure the wall protecting the sheltered life of civilization from the horrors of war a desire to remain innocent? To protect oneself from sharing the hardships that others have endured? To shield oneself from one’s own darkness and ugliness?

Perhaps our great error (or crime) is succumbing to the illusion that the civilized world can be contained, sealing off the cracks through which people could slip out to scout the dangerous unruly territories beyond and return, taking it all in so that there is no longer an outside. And so the war starts to happen here, on the territory of the civilized world.

April 10, 2022, Kyiv

Now I am in Kyiv. The city is spacious, in part because of the terrain, and to a large extent because so many people have left.

Yesterday I walked along the Dnipro, in solitude, its cloud-strewn waters beside me. I feel strength and power being on my own land.

There is a substantial checkpoint at the corner of the street. The people in my neighborhood have always been serious about defending their territory: from speculative building projects, from suspicious elements in 2014, from Russian invasion.

Coming back brought the immediate and visceral sensation that while I was, really, at home again, surrounded by familiar things and landscape and daylight, I could never return to that home I left the day that missiles exploded within hearing range.

Even before recent Russian statements calling for the complete obliteration of Ukraine in the name of “de-Nazification,” before the discovery of Russians’ brutal murders of civilians in the towns surrounding Kyiv, I called this war a genocide. It began the moment that Russia’s massive assault on February 24 sent Ukrainian people fleeing to different parts of the country (and millions across the border), splitting families, scattering communities, wrenching people from their homes and cities.

A human being is not contained in its skin; we need our places and our people to feel like ourselves.

*

There is nothing like sleeping in your own bed. The way the body relaxes. Even when it fears that it shouldn’t.

There were no air raid sirens last night.

In Lviv I tried all sorts of responses to the sirens. Settling down in the corridor with my computer was standard. Staying in bed felt defiant. Once I slept in the bathtub.

One anxious morning I woke just after falling asleep, dressed, and went down to the nearby bomb shelter. Sitting there, butt freezing on the cold pressboard bench and inhaling the dank air, I felt stupid. The risk of injury or death from an airstrike in Lviv is negligible, but you are sure to damage your health from interrupted sleep and spending an hour in the cold, which creeps through the soles of your winter boots. Minutes after returning to my apartment I am already sneezing.

Being safe is not a state, but an event. As long as it keeps recurring you can restore your energy and wits to prepare for the next time you have to think and act quickly. Why fill these moments with projections of what could happen based on memories of past suffering?

One night in Lviv I had the distinct sensation that I was back in childhood, lying in bed in the American suburbs. I would often imagine an impending break-in or fire or some other disaster I had seen on the TV show Rescue 911. Only now – when my body is primed from its own experience of air raid sirens and the threat of bombing from the sky – do I know what that feeling of danger actually was.

I’ve been escaping from the Russians since 1943.

*

When you run away you preserve the memory of your home unscathed, even if it’s decades before you return (or never). My grandmother took her entire experience of home, sealed hermetically by the abruptness and violence of her departure at the hands of Nazi soldiers, to Germany, then to England, and then to the USA.

Decades later I received a love for her homeland and its warm culture of community as well as an obsession with safety. I also inherited resourcefulness, flexibility, and a talent for getting by in new situations. Perhaps I could have been a spy were I not completely occupied with repairing this severed connection between home and security (which has taken generations).

That rupture has made us, like so many millions who went through that war, susceptible to idealizing abstractions like homeland, safety, or peace. And the devotion to these abstractions is detrimental to life, to a life lived vibrantly (in partnership with death, which will come sooner or later anyway), to political life based on freedom.

The first morning I awoke in Kyiv I sensed a process happening inside my body that was set in action before I was born. As if my primary purpose was to experience that incredibly uncomfortable feeling of going on living in your home, now in the midst of war, knowing that you are under attack and always in potential danger.

I agree wholly with my grandmother that war is something nobody should ever have to experience. But she misjudged in trying to protect me totally. Because what I’m learning now I’m learning for all the generations of my family since World War II: peace, like safety, exists in moments. Like when it’s dark and quiet at night in Kyiv.

But I feel safety in mobility (thanks to my refugee heritage). And perhaps in nothing else.

April 29, 2022, Lviv

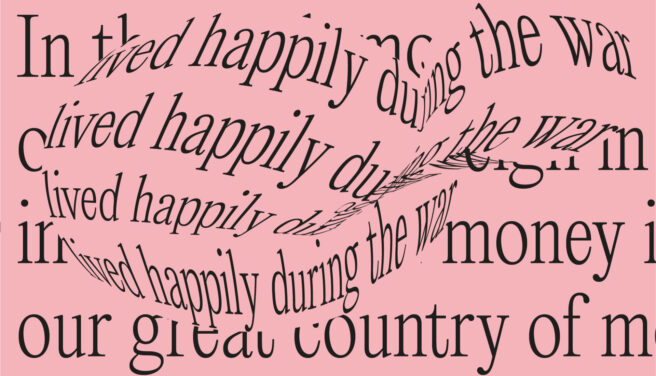

My position on Russia is clear: Russia is the enemy. Russian soldiers waging war on Ukraine’s territory must be destroyed, and any Russians who claim that Ukrainians today are somehow fighting for their freedom should fuck off.

Russia has declared its intentions to destroy Ukraine as a nation and obliterate the Ukrainian people, their language, history, and culture. To leave no physical evidence to contradict its revised version of world history.

My grandparents taught me that Russia was bad. The Russian language was ugly, with its guttaral ы and harsh Г (G). In the hyperpatriotic Ukrainian diaspora this was considered an objective fact.

But as I came of age in the multicultural US, where we were instilled with the value of tolerance, I began to wonder if my grandparents’ ideas weren’t of another time. Yes, it makes sense to fear and loathe the people who invaded your villages and killed your neighbors. But we were all living comfortably in the American suburbs, and when I went to college in New York City, I found that people with roots in Eastern Europe, like Russian Jews, were the folks I had most in common with.

It is not interesting, today, to say simply that my grandparents were right.

Instead I wonder about what was wrong with that promise of a multicultural global world that distracted its “citizens” with great international mobility and connectedness, while allowing for the rise of a country whose hunger for power and dominance could commit genocide in the name of squelching national spirit, or in their words, “denazification.”

Today Ukrainians who for years have been committed to promoting dialogue, transcending difference, to peace and harmony, are becoming more militant in their language and positions. I too am becoming more militant, not only against Russia but against anything that distracts from taking Ukraine’s battle for democratic statehood (and protection of its people from obliteration) seriously.

Now is the time to question universal humanist values, where the individual life of the civilian woman who is raped and then shot 6 times in the back with an automatic rifle is equivalent to the life of the Russian soldier who killed her.

Because that is logically valid when you make political decisions based on counting and calculating numbers (i.e., economics) instead of principles.

It is on my conscience that instead of interrogating the global order, I demurred to it. As if that global order had already guaranteed me a place where I could be myself (whatever that means) without fighting.

As the grandchild of people for whom blending in with their surroundings meant survival, I learned not to stand out, to read quickly and deftly what people expected of me and to slide by unnoticed. Instead of making demands based on where I come from or what I stand for, I was busy avoiding danger.

It was only much later that I began to sense that I actually had no idea who I am. And that that in itself is not good. You risk becoming a receptacle for evil.

Today I wonder: When I arrived in Kyiv in 2005, why did I not demand that Ukrainians in Ukraine speak Ukrainian?

They’re speaking Ukrainian now. Only after the mass Russian invasion has made speaking Russian tantamount to speaking the enemy’s language. For some people, it triggers their trauma. Others are ashamed.

What is wrong with all of us that only in the midst of Russia’s genocide of Ukrainians do we begin to respond decisively to the fundamental questions of who we are and how we want to live? Why do we need the experience and evidence of crimes against humanity to ask ourselves what “humanity” is? Philosophy used to concern itself with questions like that.

November 13, 2022, Kyiv

The 7th floor is quiet after climbing the stairs. No children screaming across the hall. No cat face – eyes flashing green in the dark – to greet me when I open the apartment door.

Now my life is structured by the schedule of rolling blackouts: 4 hours off, 5 hours on, 4 hours off… The schedule varies from day to day. Scrambling to finish my shower or an email that can’t wait till tomorrow, I anticipate the impending power cut. But the abrupt change to total darkness is always a shock.

Sometimes it goes off off-schedule. It’s confusing too when the power is on when I expect it to be off. Should I take it as a gift? Or a sign that they’re repairing the power lines and soon these regular blackouts will stop (until the next missile barrage)?

The other day I was in a dimly lit cafe since I didn’t have power or Internet at home to connect to Zoom. I was translating for an American psychiatrist consulting Ukrainian psychosocial support providers who work with people who’ve had to flee their homes. “When you’re in survival mode,” she says, “you don’t have attention and energy available for planning ahead.”

Living between blackouts has taken a toll on my health and psyche. It’s affected my friends too: each one is a bit disoriented, more anxious, deeply tired. We reach for one another for support and yet each one of us is depleted, with nothing extra to give. My friend Larisa shares a piece of wisdom from her Japanese butoh teacher: when your mind is tired, enliven your body with spirit.

*

The morning light draws me outside. Walking along the river I look into the faces of people I pass. Hardship opens me to seek companionship. Sharing a kind word with a stranger might elicit one in return. Most of the faces are closed; some acknowledge my shy smile; others transmit an anguish that stops me from blurting out “Good day!”

Civilian life in the midst of war is an uncomfortable exercise in contradiction. If being a warrior demands complete acceptance of the circumstances you are in to focus on how you can best perform your task right now, then the very actions and patterns of civilian life include a memory or residue of those peacetime conditions that are now missing. You may have no guarantee that the power or Internet will be available in the next moment, no assurance that the store or water fountain you’ve set out for will be working when you get there, but your life still consists of obligations that depend on these things.

And when you’re working in a civilian framework with people around the world who do have electricity 24/7 and do not live under constant threat of missile strikes then you too are supposed to be reliable. That’s part of the unspoken agreement that underlies any commitment to work together: that you will do your part to overcome your unreliable conditions to show up at the agreed-upon time and find in yourself the strength and clarity of mind to perform.

“Kyiv is functioning,” I said over Zoom to a roomful of Americans at a university in Connecticut. Afterward I regretted that I chose to highlight Ukrainians’ fortitude and resourcefulness in the face of adversity instead of giving them a more visceral picture of what it’s like to live mostly in the dark.

One listener asked, “How can we help Ukrainians with electricity?” While the panelists from the Dnipro city council talked about generators, I wondered why this question made me mad. “Look, Ukrainians are coping and will continue to persevere,” I added, “But the issue is not in the number of generators we have. The issue we need your help with is making it impossible for Russia to keep hitting our critical infrastructure with missiles.”

For all their genuine care and commitment, most Americans still treat what is happening in Ukraine as a misfortune.

*

Walking along the dark streets of Kyiv one evening it hits me: the world that we’ve built – globally interconnected and interdependent – depends on us getting along to function. And this interdependence has reached a scale where compromise between nations (or corporations) threatens the freedom of people to take care of themselves and organize their life together in contact with one another at the scale of local communities (and sovereign nations).

When the war is happening onscreen, it’s easy to exercise your logical reasoning in the privacy of your own mind and favor abstract solutions of a global scale or to imagine ways to help alleviate suffering in the most effective way possible. It’s only when you take a step to get involved do you hit up against physical realities – size and weight, distance and time, cost and mortality. Every logistical operation involves dealing with people and the systems they’ve created, varied and specific to every culture.

Kyiv, like many Ukrainian cities, still has city-wide centralized heating. This is but one holdover from the Soviet Union’s policy of centralized control over all aspects of life. Today Ukrainians are thinking about localizing energy production and consumption at the scale of building or neighborhood. While we fight to secure and protect the freedom to practice our own political culture, we in Ukraine face a no less daunting challenge: noticing our own deep-seated Soviet attitudes toward power, control and cooperation and refusing to perpetuate them.

*

One morning I hear a loud whistling as I walk through the park; it’s intermingled with bird sounds, but distinctly human. On the way back home I pass the culprit and can’t help but grin. He responds with traditional Soviet brusqueness: Whistling fortifies the spirit.

(This is an excerpt from A Kind of Refugee: The Story of an American Who Refused to Leave Ukraine, forthcoming from ibidem Press, 2024)