Savanna. A hunter is out hunting. Suddenly, he sees a lion. He starts aiming and almost pulls the trigger when the lion tells him, “Don’t shoot! I am Nikolaevich Tolstoy!”

(Czech anecdote told by Oleksandr Stukalo; a wordplay based on the name “Lev” and the word “lion,” which are written in the same way in many Slavic languages)

I am an hour and a half through a Zoom call with the representatives of a Western European cultural institution, and we are talking about Tolstoy. It was meant to be a regular quick work call about organizing a series of panel discussions on Ukrainian culture and decolonial optics. But yet here we are — an hour and a half later (I am not joking, the free version of Zoom has already made us reconnect twice), and we are still talking about Tolstoy. Or, rather, listening to a monologue about how inappropriate it would be to cancel Russian culture and how the world — and the speaker in particular — would not be able to live without Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky, and — well, you know — Tolstoy.

I have brought it upon myself in a way. Earlier, I submitted a proposal for a series of talks with the names of potential speakers. One of them was Volodymyr Sheiko, the head of the Ukrainian Institute and the author of the open letter calling foreign cultural institutions and cultural workers to suspend cooperation with institutions in Russia, boycott Russian events, refrain from showing and supporting Russian culture and art, and so on. And all hell broke loose.

For an hour and a half (and still far from the end), I have been listening to the arguments about the significance of Russian culture, its lack of connection to the ongoing war, the growing number of cases of “Russophobia” in Europe, the “brave” Russian ballerina who escaped the Nazi homeland and got herself a nice job in the Netherlands, and the “even braver” woman with a poster in allegedly live propaganda broadcast on Russian TV. And, as you may have already guessed, about Tolstoy.

The discussions were meant to give voice to the Ukrainians — and I am trying to speak during the Zoom call, but it does not go well at all. I try to explain that behind our calls for cancellation is the dire need to start the process of deimperialization and, ironically, denazification of the Russian cultural heritage, both classical and contemporary — which was also mentioned in the letter written by Sheiko. That for centuries, the narratives imposed by this culture have excluded and dehumanized every other culture subdued by Russian (including Soviet) imperial conquests. That so many people and so many nations have been deprived of their voices for too long, which has always resulted in bloodbaths, and one of them is happening right now — and this has to end. My colleague, also Ukrainian, joins in and tries to throw in several sentences about the last three centuries of cultural and physical genocidal attacks from Moscow on our people and our identity.

“But he said CANCEL.” “But a university in Milan announced that they would cease studying Dostoevsky and later reversed this decision.” “But it is madness to stop performing Tchaikovsky.” “But Mayakovsky.” “But Rodchenko.” “But Tolstoy.” Eventually, I have give up and become a passive radio listener while the monologue goes in circles.

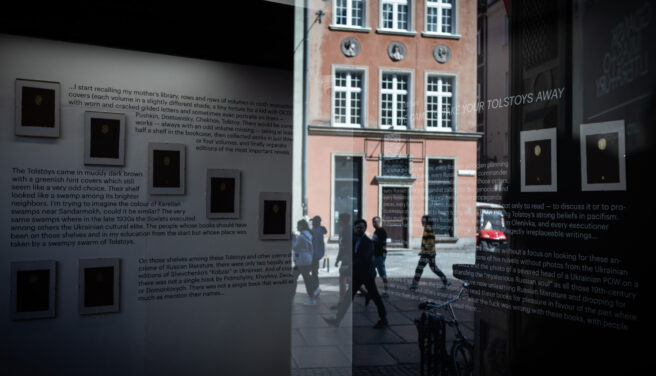

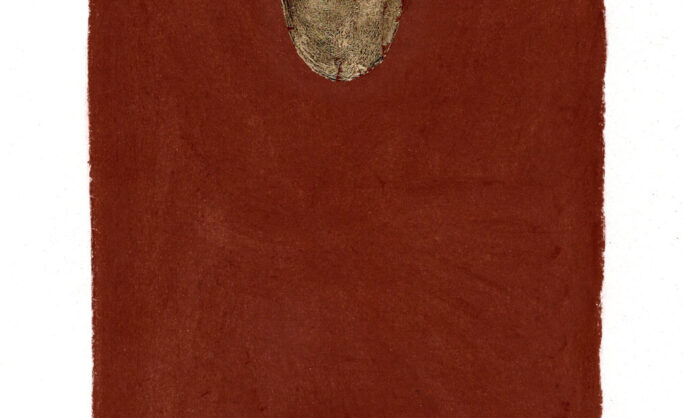

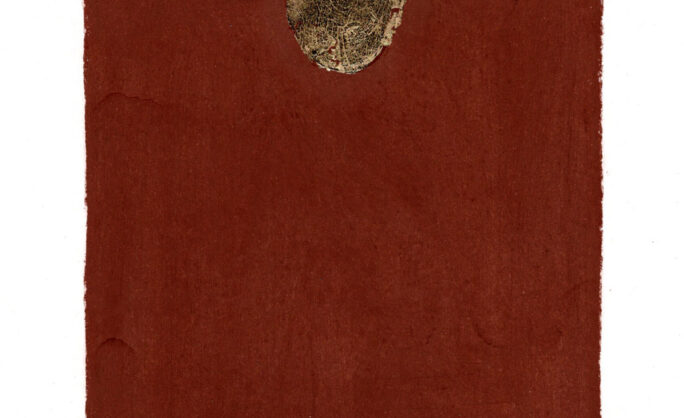

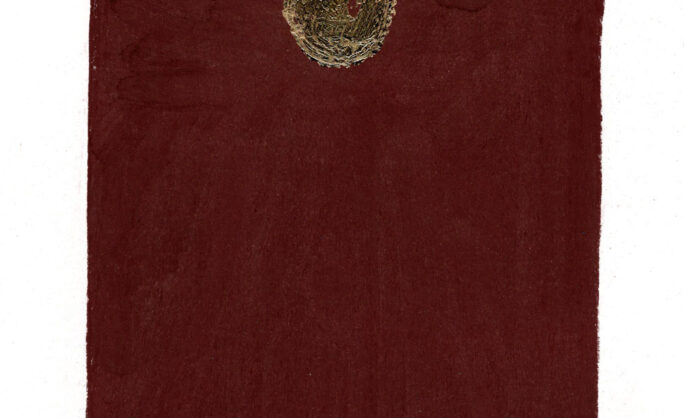

I slowly doze off and start recalling my mother’s library; rows and rows of volumes in monochrome cloth covers (each book in a slightly different shade, a little torture for a kid with OCD) with worn and cracked gilded letters and sometimes even portraits on them — Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy. There would be complete works — always with an odd volume missing — occupying at least half a shelf in the bookcase, then collected works in just three or four volumes, and finally, separate editions of the most important novels.

The Tolstoys came in muddy dark brown with a greenish hint covers, which still seems odd. Their shelf looked like a swamp among its brighter neighbors. I am trying to imagine the color of the Karelian swamps near Sandarmokh; could it be similar? The very same swamps where in the late 1930s, the Soviets executed the Ukrainian cultural elite, among others. The people whose books should have been on those shelves and in my education from the start but whose place was taken by a swampy swarm of the Tolstoys.

On those shelves among these Tolstoys and other crème de la crème of Russian literature, there were only two heavily worn editions of Shevchenko’s Kobzar in Ukrainian. And, of course, there was not a single book by Pidmohylny, Khvylovy, Zerov, or Domontovych. There was not a single book that would as much as mention their names — after all, it was a typical library of a typical member of Soviet technical intelligentsia, not some illegal samizdat collection of dissident books.

During my school literature classes, no one would mention these names along with many others, not to mention those we might still not even know about. It was in the late 1990s, several years after the USSR fell apart, but we still had to go through a course on Russian literature alongside a much more modest course on Ukrainian literature. Back then, the Ukrainian literature course was still very much based on the Soviet selection of safe and neutered works. There were suffering peasants and folk legends, and when it came to the 20th century with the works by Vasyl Barka and likes, who used to be banned in the Soviet times, not much would really change aside from peasants doubling their sufferings.

The Russian literature course was way different. There was imperial grandeur and development of the literary tradition. The program was almost entirely taken from the Soviet times and crafted carefully to justify Russian dominance — even though formally in independent Ukraine, there was no need to reaffirm it anymore. We would recite Pushkin’s views on Russian conquests in Poland and Ukraine, look at the imperial wars in the Caucasus region through Lermontov’s eyes, and even delve into endless volumes of Sholokhov’s communist propaganda. And, of course, there was Tolstoy.

We would read volumes of Tolstoy’s works, listen to lectures on how Tolstoy’s pacifism could be traced through all his writings, discuss it in class, write essays on Tolstoy and the fate of the Motherland (and no one ever cared to explain to us that it was somebody else’s Motherland). I think we even had to learn the fragment about the sky of Austerlitz by heart. Just like our parents did before us and their parents before them too. Just like kids our age did in every school in every city, town, and village in Russia. Just like they still do, I assume — no reason to expect anyone would have challenged the existing order of things.

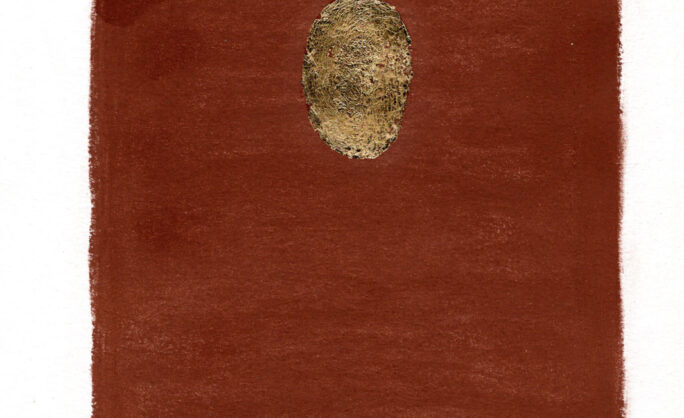

Just think of it — at some point in their lives, every Russian politician planning the occupation of Ukraine, every Russian military commander giving orders and every Russian soldier obeying those orders, every Russian state propagandist calling for the genocide, and every Russian citizen happily swallowing those propaganda pieces, every fucking one of them had to read Tolstoy. And not only to read — to discuss it, to produce essays on it, or at least to listen to the teachers explaining Tolstoy’s strong beliefs in pacifism. Every murderer in Bucha, every looter in Irpin, every torturer in Olenivka, and every executioner in Popasna had received an obligatory infusion of Tolstoy’s allegedly irreplaceable writings.

And I cannot stop asking myself what they really saw on those dusty pages — and in that endless sky of Austerlitz? What kind of knowledge was passed on to them with those words? Did they see something entirely different from what Western intellectuals see when they read the exact words in English, French, or Portuguese? Did Tolstoy fail at promoting the idea of pacifism just like he failed at not abusing his wife?

These questions have no answers — and I cannot imagine the future of Russian studies without looking for these answers. Just as I cannot imagine new foreign editions of Tolstoy’s novels without photos from the Ukrainian war on every second page. It is the year 2022, and the photo of the severed head of a Ukrainian POW on a stick is now just as important for understanding the “mysterious Russian soul” as all those 19th-century novels. Learning Russian literature might require now unlearning Russian literature and dropping for many years, if not forever, the part where you read these books for pleasure in favor of the part where you ask yourself — and others around you — what the fuck was wrong with these books, with people who wrote them and with people who read them.

We cannot forbid you to read Tolstoy (and that was never the intention), we cannot burn your copies of Voina i mir (and that was never the intention either), but we can — and, oh God, we will — take away your joy of reading his books for good.

Afterword

It took me quite a while to finish this text, to do the drawings, and then to make sure it was worth publishing. Altogether, half a year had passed since the beginning of this story, and the text was still in draft. And then, in November 2022, Russian rockets hit Nikopol, a town just across the Dnieper River from the nuclear power plant in Enerhodar — again, like so many times before. But this time, a semi-burnt book was found inside one of the shells. A book by Tolstoy, ironically published in Kharkiv back in 1986. So much for “Don’t shoot, I’m Nikolaevich Tolstoy”.